US Fuel Export Retort, but Global Market Short

US exports of refined petroleum products have boomed and are a critical component of the increasingly strained global trade in key fuels, but remain a tempting target for political attacks

This overview of US refined product exports is part of my ongoing research on the North American oil & gas industry, which will be added to my North American Oil Data Deck to join similar analysis on Canadian and Mexican petroleum trade.

Reminder that paid subscribers also have access to a recorded voiceover of this post for easy listening.

If you’re already subscribed and/or appreciate the free chart and summary, hitting the LIKE button is one of the best ways to support my ongoing research.

The White House is, once again, reportedly weighing a ban or restriction on the export of US refined petroleum products—while it remains a tail risk, the consequences would be so dire for US consumers, allies, and the global economy writ large that it warrants an exploration of current US petroleum product trade.

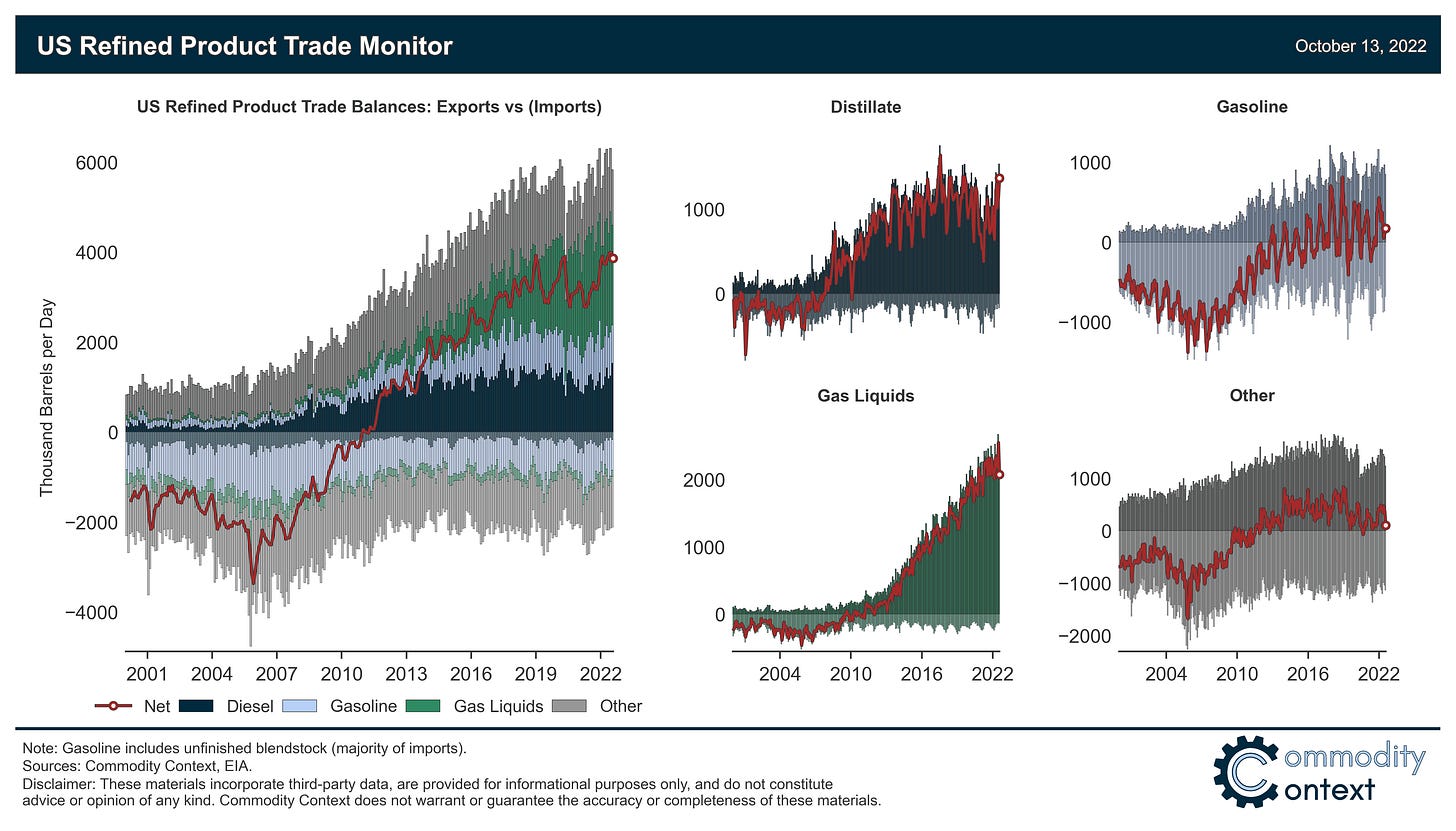

Over the last decade, the US has become the world’s preeminent exporter of petroleum products and shipments abroad have risen three-fold on the back of the rising domestic surplus of high-value petroleum products.

While banning exports may seem like a tool for lowering gasoline prices at the pump, the story is a bit more convoluted: domestic transportation, both inland and via water, faces economic, legal, and practical constraints and, ultimately, is just not enough to replace the need for foreign gasoline imports entirely.

Meanwhile, it’s reasonably straightforward to understand why cutting more than a million barrels of diesel exports during a global diesel supply crisis—and we would expect a massive ripple effect abroad as implicated countries (think Mexico, Brazil, Chile, etc.) searched for, and bid up, higher priced alternatives.

It is less clear if any such export ban would impact what can only be described as booming HGL export growth, which is up roughly eight-fold over the past decade; with this, the US’ market share in the global HGL trade will continue to grow over time so long as policy blocks don’t get in the way.

Ultimately, a ban remains an extreme tail risk scenario, but the US has grown into an integral part of the global refined petroleum product trading system and, like with crude before it, there seems to be a temptation for politicians to take aim at these exports as the reason for high domestic prices.

Once upon a time, not all that long ago, the consensus view was that the US was destined to import an increasingly large portion of its hydrocarbon needs. Instead, the US has become the world’s preeminent exporter of petroleum products, with shipments abroad rising three-fold over the past decade. This abrupt about-face has come on the back of the tight oil and gas revolution as well as the rising domestic surplus of high-value petroleum products.

Leaving the 2015 repeal of the crude oil export ban for another day, let’s, instead, focus on the other export ban currently making the rounds: the White House is reportedly weighing, once again, a ban or a restriction on the export of US refined petroleum products—an energy policy that I have repeatedly called the single worst in a dizzying array of recent bad ideas. I say this because such a ban would be detrimental to the majority of US motorists, US allies, and the fragile global economy. While such a ban remains an extreme tail risk scenario, it’s important to understand why it’s such a terrible idea by first understanding the US’ position in the global petroleum trade.

In this post, I’ll break down the trading patterns underlying the three big components of current US petroleum product export flows (gasoline, diesel, and hydrocarbon gas liquids (HGLs))—each of which has seen domestic surplus supply grow markedly over the past decade.