Oil Bullish on the Streets, Bearish in the Forecast Sheets

Looking at the gap between oil market sentiment and monitoring agency outlooks

Despite widely bullish crude sentiment, the major monitoring agencies expect oil market pressures to ease over the coming months and conditions to flip, at least temporarily, into surplus through 2022.

Five common assumptions can be seen as driving these more bearish forecasts: 1) rebounding US shale, 2) further unwinding of COVID-era OPEC+ cuts, 3) all-time high production for non-OPEC producers outside the US and Russia, 4) unchanged Iranian and Venezuelan oil sanctions, and 5) a complete post-pandemic demand recovery.

Together these assumptions suggest that market sentiment may be getting ahead of itself relative to the fundamental outlooks of the major monitoring agencies.

If the future oil market does turn out to be tighter than the agencies’ forecasts, it’ll come down to one of the five common assumptions being wrong (e.g., shale stalls out, OPEC+ falls further behind, etc.).

Oil prices are above $90 per barrel for the first time since 2014, and the bulls are feeling validated. Few are saying that oil could hit $100 per barrel anymore—it’s more or less assumed that it will at some point through 2022—while the could has shifted to $150 or even $200 per barrel targets.

It’s not hard to see why: prices are experiencing a historic rally, visible crude inventories are plunging, OPEC+ has repeatedly missed its planned production additions, US tight oil production remains well below pre-pandemic levels, and demand growth continues to be robust.

But while boom followed COVID bust, all three major global oil market monitoring agencies continue to forecast a return of at least temporary (OPEC) if not longer-lasting (EIA/IEA) oversupply conditions. This chasm between financial outlooks and the monitoring agencies’ forecasts leaves considerable room for debate.

So, what exactly are we debating? With crude prices this volatile and a near-certain tidal wave of oil-related headlines coming our way over the coming months, I think it’s helpful to understand what specific assumptions the monitoring agencies are making to arrive at their relatively bearish—or at least less bullish—market outlooks.

These forecasters are all relying on five common assumptions: 1) a decisive bounce-back in US tight oil production, 2) that OPEC+ manages to return most but not all of its planned barrels, 3) that non-OPEC+ producers outside the US see all-time high output on the back of growth (e.g., Canada, Brazil, and Guyana), 4) there’s no major movement on Iranian or Venezuelan oil sanctions, and 5) that demand returns to pre-COVID levels but growth gradually begins to slow again as base effects wear off.

In this piece, I’ll look very briefly at each of these common assumptions, with the intention of digging into certain ones more deeply over the coming weeks. I do want to emphasize that these are not my forecasts because I don’t currently publish forecasts, but keep your eyes peeled for more coming this year! And while I think the collective forecast is notably more bearish than the sentiment I’m observing, it is far from a call for crude prices to collapse—more like an easing of upside pressures with the possibility of a very modest step back.

For this analysis, I’ll be digging into the forecasts of OPEC (the Monthly Oil Market Report (MOMR)) and the EIA (the Short Term Energy Outlook (STEO)) because these are both publicly available and free. I’m hopeful that the IEA will soon follow suit if member countries agree to fund the budget gap (read more here), so feel free to email your national energy minister, etc. and let’s get that initiative funded!

1) Shale Strikes Back

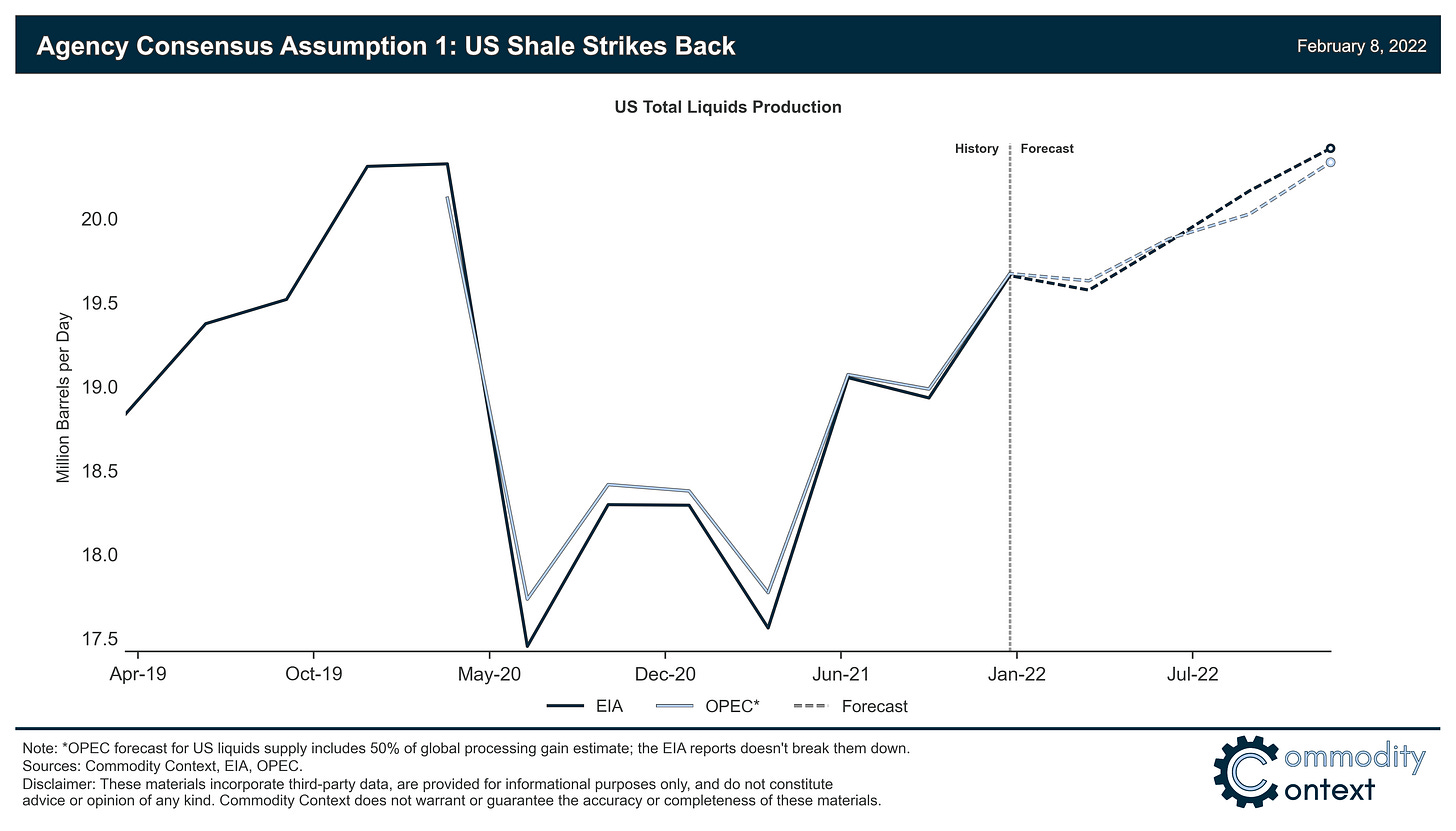

The single most important forecast variable for oil outlooks right now—and likely much of the coming decade—is the assumed performance of US shale producers.

At current prices, virtually all major US tight oil producing regions are profitable; so, the question remains: why aren’t we seeing faster growth already? Production remains 1.3 million barrels per day (MMbpd) below pre-pandemic levels and, as I discussed here, is being effectively subsidized by a rapid drawdown of drilled-but-uncompleted (DUC) wells. To see growth, there needs to be a lot more drilling and activity broadly.

Despite this lacklustre recent record, both the EIA and OPEC continue to expect US producers to fall back on old ways: opening the investment spigot—maybe not all the way, but certainly wider—and growing production by more than 1 MMbpd through 2022.

Don’t agree with that US production outlook? Mark down (or up) your market balance forecast by the amount you think those forecasts will miss and repeat over the next four assumptions.

2) Most OPEC+ Crude Returns, Russian Production Reaches All-Time High

As I wrote back in July, the current oil market exists in the shadow of the COVID-era OPEC+ production cut. The expanded producer group very literally saved the oil market at the beginning of the pandemic, cutting collective output by 9.7 MMbpd to offset lockdown-related demand losses. The return of that near 10% of global supply has been top of mind—and we’re getting close but not quite to pre-pandemic levels.

The EIA forecasts that OPEC crude oil production will rise a further 1.4 MMbpd through 2022 but will stop about 1 MMbpd short of fully unwinding its full contribution to the OPEC+ cuts (my thanks to the EIA STEO team for actually publishing a forecast for OPEC crude output). This forecast is a reasonable middle ground between fears of OPEC quickly running out of spare capacity and the demonstrated challenges in lifting crude output in OPEC members like Nigeria and Angola that are unlikely to return to previous production levels anytime soon.

Russia was the other major component of the market-saving OPEC+ deal, accounting for 2.5 MMbpd of the initially committed 9.7 MMbpd, and both OPEC and the EIA expect Russian production to reach all-time highs through 2022 as the OPEC+ deal wraps up. This, to me, seems even more optimistic than the OPEC assumption, but we’ll dig deeper into Russia in another post.

3) Non-OPEC Supply ex-US/Russia Grows to All-Time High

Most of the supply-side attention is rightfully on US shale and OPEC+. Still, it is expected that non-OPEC production outside the US and Russia will contribute upwards of 1 MMbpd of additional petroleum supply this year. The new all-time high would be largely on the back on growth in Canada, Brazil, and Guyana, and is especially notable given that production in this block has remained pretty darn flat since the 2014 oil price collapse.

4) No Movement on Iranian or Venezuelan Oil Sanctions

While the other assumptions are mostly gradients (e.g., how much will US shale growth), the trajectory of sanctions regimes against Iran and Venezuela are binary, or at least stepwise. That is, we’ll either see movement or we won’t—and agency consensus is that we won’t. This was a reasonable expectation, but news over the weekend that the Biden administration was looking to re-enter the JCPOA (i.e., Iran nuclear deal) makes it less of a slam dunk.

Sanctions against Iran and Venezuela are collectively costing the oil market 1-2 MMbpd depending on how you’re counting—these are potentially big numbers when we’re talking about forecast surpluses of only a few hundred barrels per day. Additional unsanctioned Iranian and Venezuelan barrels are unlikely to be returned before the end of 2022, but the return of one or the other could, all else equal, tilt the oil market into more decisive oversupply.

5) Demand Back to Pre-COVID level, But Doesn’t Boom

Of course, each of the above supply assumptions could be for naught if the post-COVID demand recovery stalls out—either from simple exhaustion (aren’t you tired?) or due to a recession prompted by central bank tightening. None of the agencies expect this type of scenario, though OPEC assumes a relatively faster trend growth (4.2 MMbpd y/y in 2022) coming out of COVID compared to the EIA (3.6) and IEA (3.3), which goes a long way to explaining why OPEC alone expects to end 2022 back in deficit.

Put all these assumptions together and you arrive at an annual average oversupply of roughly 500 kbpd from the EIA and a more-or-less balanced market for the year from OPEC. These forecasts aren’t terribly bearish, but they don’t scream $150 or $200 per barrel crude and getting to those unprecedented levels would require at least one of these common assumptions to be wrong. Now go try and figure out which one it will be—happy forecasting.

Clicking the LIKE button is one of the best ways to support my research.

Shout out to you for your excellent interview on the Grant Williams Doomberg podcast . Everyone should give it a listen. What is your opinion of Charlie Mungers simple view that we should leave our hydrocarbons in the ground for a later day ? And your opinion on the Montney condensate producers ?

Thank you for this. It was a pleasure to read, and the identification of key variables is very helpful. In particular, I wonder - what do the agencies know about US production ramp-up that I don't?