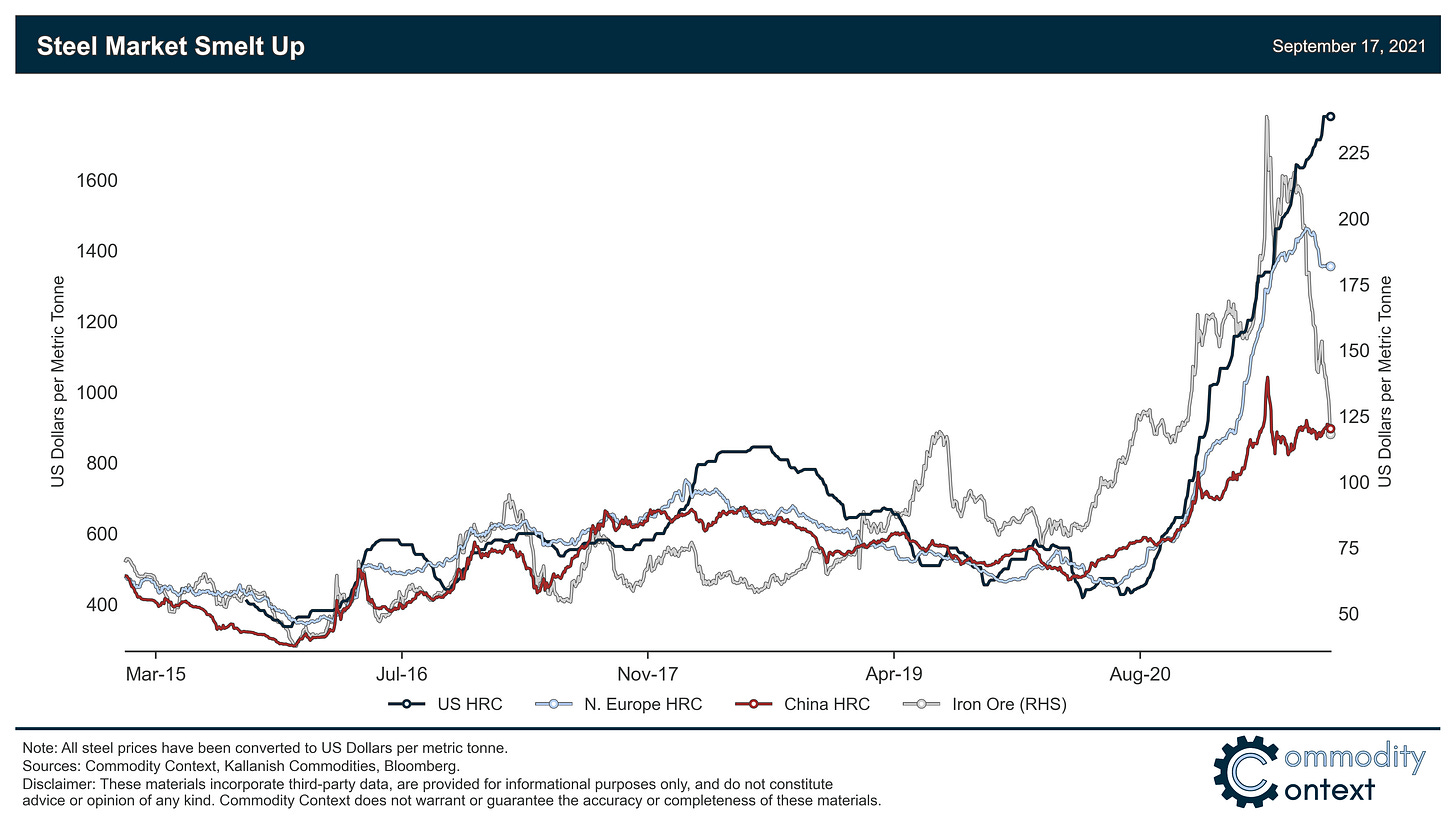

Steel prices rallied around the world but have gone higher and for longer in the US.

The rally began in China with strong real estate investment and manufacturing activity, pushing Chinese steel production higher and pulling up the price of feedstocks like iron ore.

What began as a cost-related price increase in China quickly turned into a global supply chain crunch and rush for metal in the US and Europe, where prices rose to all-time highs in 2021.

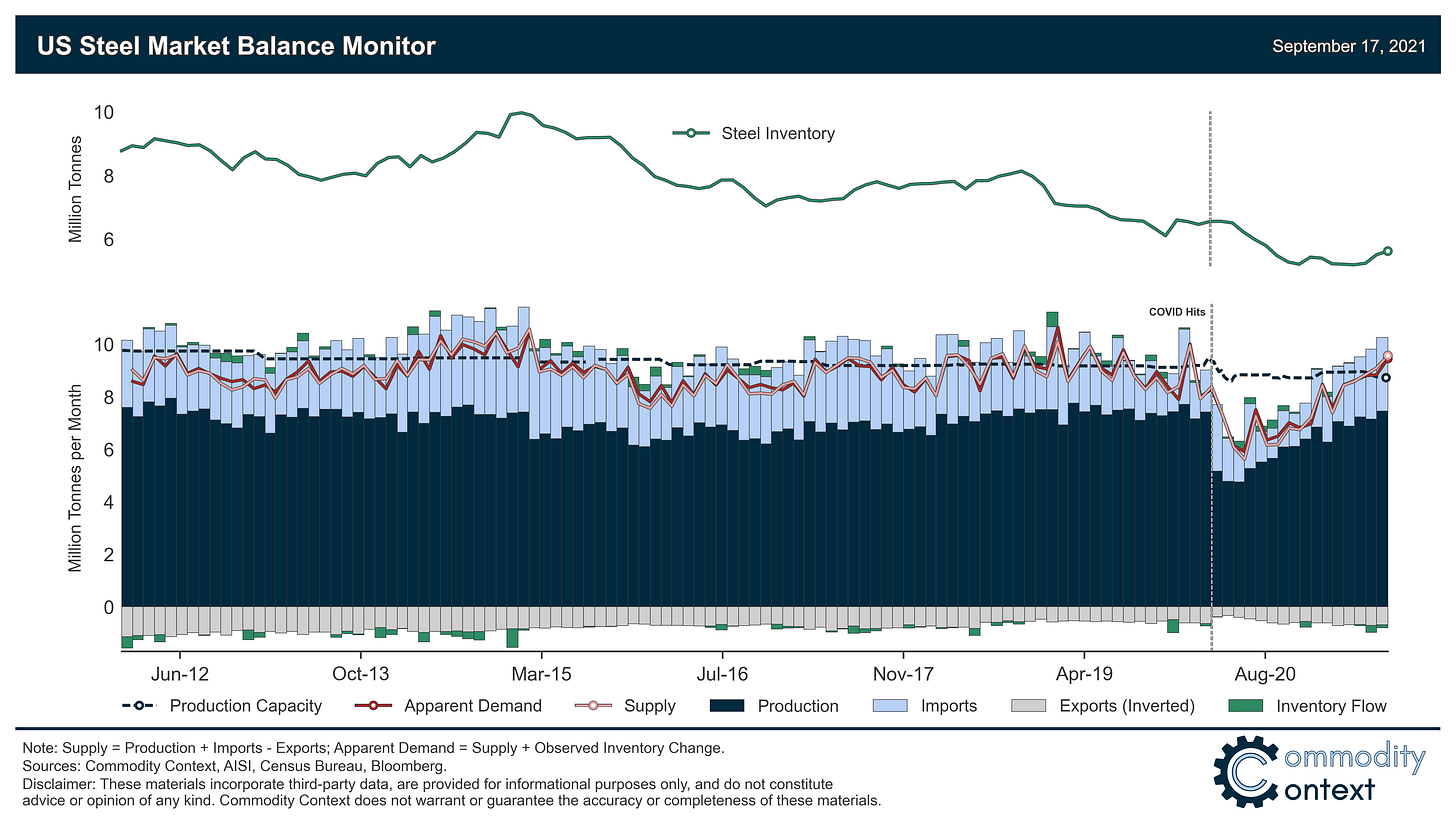

US steel prices continue to mint fresh all-time highs while inventories are only starting to rise from all-time lows.

While the bulk of the price spike is likely behind us, steel prices should not collapse in the way we’ve seen across lumber or iron ore markets. Record-low inventories still need to be rebuilt and demand still looks reasonably resilient.

Following a now-familiar pandemic bullwhip pattern, steel prices around the world rocketed higher in the second half of 2020 and set record upon record through 2021, particularly in the United States. A quintessentially ubiquitous commodity, the steel industry had previously suffered from years of excess global capacity, lacklustre demand, and falling prices. Then COVID changed everything. Like the wild lumber spike earlier this year, the exploding prices of and lead-times for everything steel—from wall panels to rebar—have pushed up costs and compounded bottlenecks further downstream.

So, what’s going on with the steel market and why are steel consumers in the US facing an especially tight situation?

Off the bat, it’s important to recognize that steel markets are highly regional. Steel is heavy and expensive to transport, which creates natural trade frictions that favour local producers (at least to a point). This is particularly exaggerated right now as shipping costs experience their own bullwhip crack to all-time highs. Also, steel industries tend to be political: steel production typically employs politically valuable, often unionized, constituencies concentrated in key electoral jurisdictions, which frequently leads to protectionist policies like of tariffs and other trade barriers. Global steel prices tend to move broadly together but given these interregional frictions can deviate significantly between China, the US, and Europe, particularly in the short term—these days, they are deviating by A LOT.

All Metallic Roads Begin in China

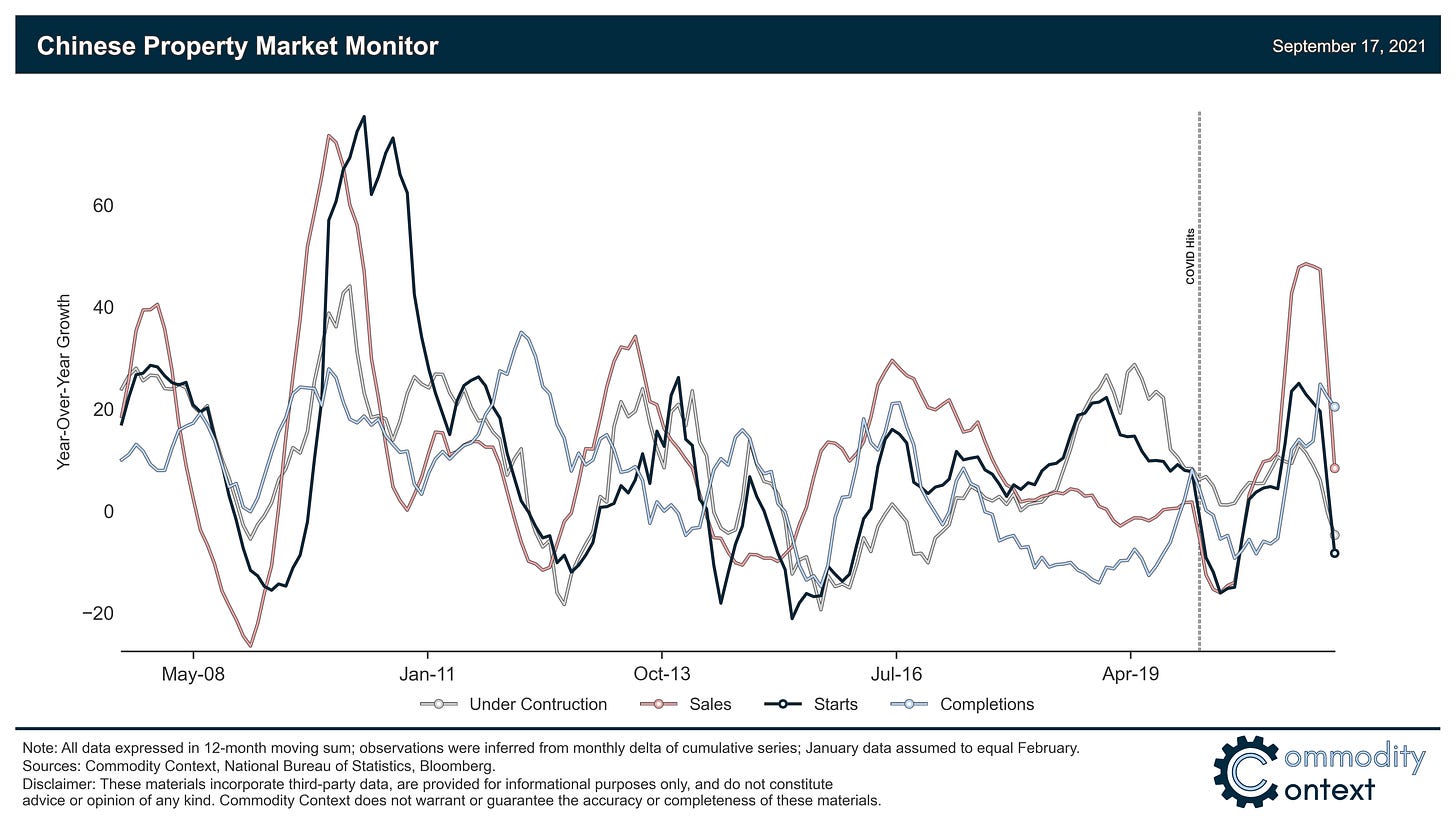

As with other industrial metals, China dominates the global steel industry, producing and consuming about half the world’s total tonnage (see my discussion about Chinese copper demand). The pandemic’s initial effect in China mirrored the global experience: industry froze up, real estate sales fell at the fastest pace since 2008, and construction activity slowed considerably. Steel demand slumped and Chinese inventories hit an all-time high in March 2020.

But then China underwent the world’s first COVID economic rebound—the very first crack of the whip if you will. Real estate investment got supercharged by cheaper credit and export demand soared as locked-down consumers around the world began ferociously clicking online order buttons en mass. This torrent of steel-intensive activity pushed both apparent Chinese steel demand and domestic production to fresh all-time highs by mid-2020.

To satisfy the rush on steel, China imported record volumes of iron ore beginning in July 2020, which caught the seaborne market off guard. Iron ore miners were, as everyone else, expecting a pandemic demand recession and had suffered COVID-related shutdowns at mines and through the shipping industry. With the run up of surprisingly strong demand from China against this weakened global supply, seaborne iron ore prices boomed to all-time highs by Spring 2021.

Steel and iron headed higher together until they both peaked in May 2021. From there, Chinese steel prices fell back slightly and ultimately plateaued at still-high levels around $900 per tonne, supported by government mandated production cuts. While less steel production is good for domestic Chinese steel prices, it’s been terrible for iron ore prices, which have continued to collapse.

China now faces two opposing trends that will determine the course of steel prices over the next year. The steel-positive trend is the aforementioned production pullback: Beijing doesn’t want 2021 steel production to exceed 2020 levels, partly in pursuit of its decarbonization goals as well as a strategy aimed at reducing raw material prices, where they continue to have an acute effect on iron ore. The steel-negative trend is construction-related demand: real estate activity indicators are already diving and the ever-worsening condition of property behemoth Evergrande (way too big a story to get into now) presents a significant tail-risk of steeper demand losses.

The US Steel Rally Never Ended

While the rally rolled over months ago in China and weeks ago in Europe, US steel prices keep heading higher—currently at around $2000 per short ton or almost double the previous high set back in 2008.

US apparent steel demand began outstripping supply in June 2020; but unlike in China, domestic US mills were relatively slow to react. In fact, US steel production has yet to outpace pre-COVID levels while demand is as strong as it’s been in years. Even since the pandemic began, the US steel industry has consolidated and production capacity has fallen to the point that production capacity utilization—a standard way of measuring how hard the industry is running—is running above 85%, its highest level since 2008 despite the still-depressed production volume. The US steel sector doesn’t typically stray far above that 85% mark; we haven’t seen 90% utilization since before the Great Financial Crisis.

If we’re ever going to see mills push their limits to maximize output, however, now is the time—with prices at all-time highs and the Trump-era steel tariffs remaining in place. Still, it will take time to refill severely depleted inventories even if producers can rise to meet demand. Imports could rise, but probably not until shipping bottlenecks and/or tariffs are unwound. In the interim, Canada has come out as an obvious winner with steel exports to the US rising to levels, which, if maintained, would also be the strongest since 2008.

There is always the possibility of a demand-side correction: another COVID wave, a wearing-off of the general post-pandemic sugar high, or a reopening that shifts spending from goods toward services to cool manufacturing demand. But it’s more likely that the bullwhip will have more than one crack. As some bottlenecks ease—in semiconductors and auto manufacturing, for instance—demand in currently depressed but typically important steel demand drivers will snap back, adding subsequent waves to the materials demand pull.

Absent a severe unwinding of China’s real estate sector (always a good caveat), Chinese steel prices will continue to trade sideways and exert gradual downward pressure on prices elsewhere. While US steel prices may continue rising for a short time longer, it is likely that the bulk of the price spike is behind us as inventories begin to slowly rise again. However, it also seems doubtful that prices will collapse as quickly as we saw in lumber or iron ore markets, which fell almost as quickly as they rose. Record-low inventories still need to be rebuilt and demand is likely to remain relatively robust—even if we begin to see weakness in currently-strong sectors, we will see additional bursts of demand from sectors like the auto industry as the debottleneck.