US Shale Patch’s Lackluster Recovery is a Problem for the Post-COVID Oil Market

US tight oil production has materially underperformed the price recovery and that’s worrying for the period after OPEC+ has completed its scheduled COVID-era cut easing

As the largest source of pre-pandemic production growth, market participants and spectators alike are looking to the US shale patch for the final leg of the global oil market’s complete recovery.

US producer recovery continues to be surprisingly weak despite the current high pricing environment. The Permian basin may be posting all-time highs, but all other major oil-dominant shale regions continue to languish.

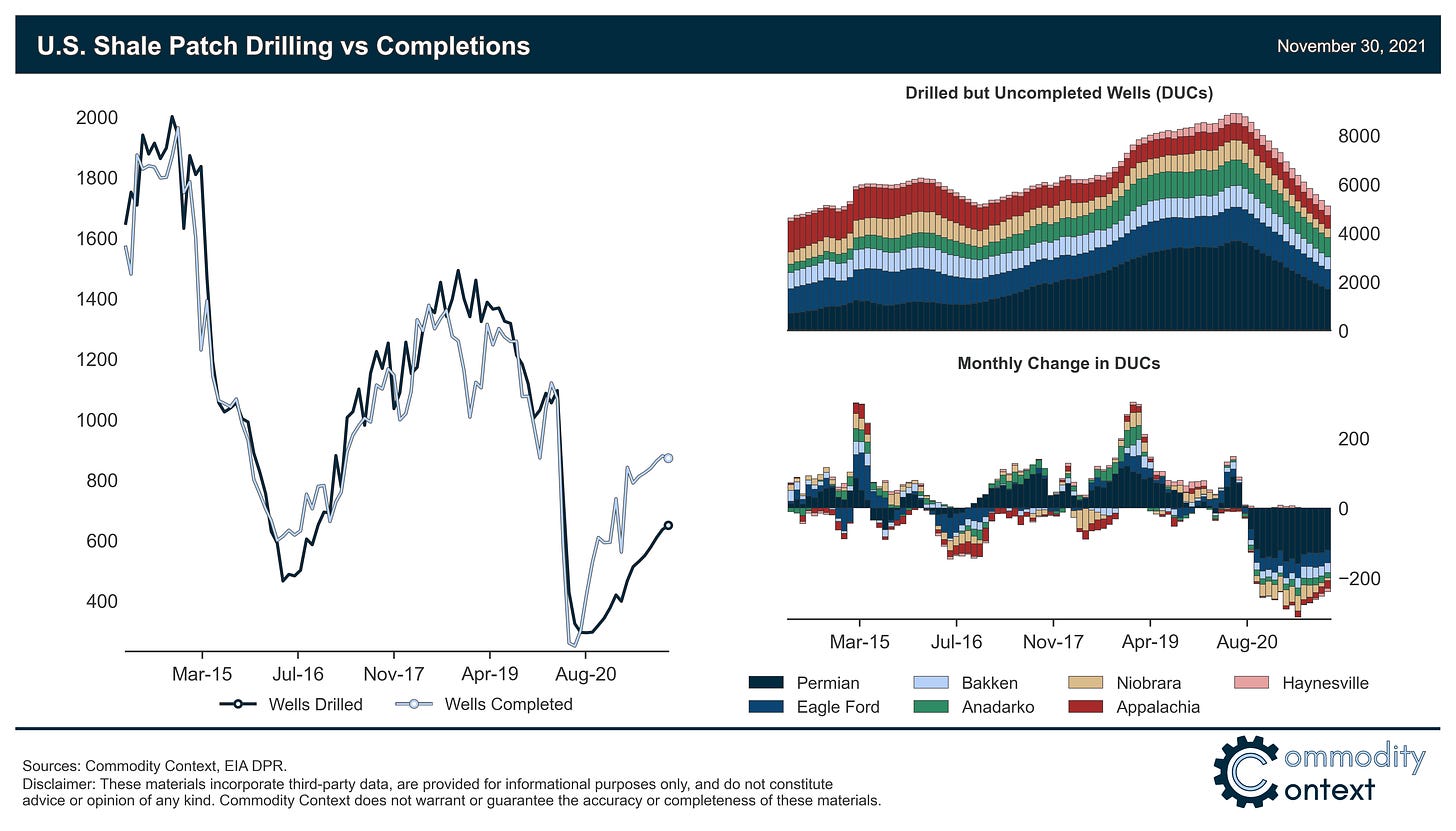

Moreover, productivity is actually worse than it first appears: most realized production gains, including those in the Permian basin, are largely subsidized by the drawdown in DUCs, with far too little drilling to support future output.

To supply the crude that will very likely be demanded by the market, US shale will require more investment and a much stronger rig deployment than we’re currently seeing, a reality made only more challenging by the Black Friday oil price selloff.

The future production trajectory and price sensitivity of the US shale patch remains the single most important question to the medium-term future of the global oil market. Of course, there are more pressing immediate concerns, like OPEC+ meetings or the latest COVID variant, and more existential long-term questions about climate mitigation policy and accelerated demand destruction.

But by the time we get to the end of next year and into 2023, we are hopefully going to see demand growing at a reasonably brisk organic pace once again. OPEC+ will have completely unwound COVID-era production cuts, leaving a very thin buffer of spare capacity. The incremental supply torch will then pass to non-OPEC+ producers, the most prolific of which is obviously the US shale patch. Sure, we can expect modest growth from Canada, Brazil, Guyana, etc., but the US accounted for the bulk of pre-COVID oil production growth and it will remain the heaviest lifter outside OPEC+ going forward.

You see, it was not that long ago that the unrelenting growth of US tight oil production was an anvil around the neck of the oil market. The $40-60 “shale band” felt increasingly like an iron law, at least for any period stretching longer than a month or two. If prices rose above that $60 per barrel threshold—and even often when they didn’t—US shale production would grow output at a truly voracious pace. Over the course of 2018, total US crude production grew by a truly staggering 2 million barrels per day (MMbpd), alone adding nearly twice the total global demand growth that year.

Easy come, easy go, however. US crude output fell by about 2 MMbpd in 2020 to an average of 11 MMbpd. That quick reaction time in response to collapsing prices is part of what makes US tight oil production so disruptive and, theoretically, self-regulating—an economic swing-producer of sorts, but tracking prices via quick-return investments and quick-decline wells rather than by government fiat. (To be clear, Saudi Arabia and to a lesser extent allied countries within OPEC+ are the only true “swing producers” within the current market, because their production can be explicitly modulated by policymakers.)

Today’s issue is that we have not seen the type of bounce back that would have been expected from the pre-pandemic shale patch. US production is only up to around 11.5 MMbpd, which is a recovery of barely one-quarter of its COVID losses despite WTI spending a solid month above $80 per barrel. This lackluster shale recovery is also why I feel that the Biden administration’s efforts to talk/press down the price of crude will be ultimately self-defeating. The Black Friday $10 per barrel oil price rout only makes this needed US producer recovery that much more challenging.

For ease, all US production statistics here refer to crude oil rather that total liquids. Virtually all the data behind the charts and discussion in this piece have been taken from the EIA’s Drilling Productivity Report (DPR), a high-level model of US basin-level oil & gas production efficiency trends. This data is far from perfect but provides a great first look at differences within the US oil & gas recovery—I hope to follow up this analysis with further, more detailed drill downs (every pun intended).

Permian Basin and the Rest

In aggregate, the US shale patch production recovery has notably underperformed the recovery in crude prices. Whether that lackluster recovery has been driven by the fabled “producer cashflow discipline”, regulatory burden, or ubiquitous supply chain challenges is a question for a different day but we’ve already seen a considerable regional differentiation. The US shale patch is far from a monolith: in the Permian basin, for example, producers are setting fresh all-time highs, while the rest of the oil-dominant shale regions remain down 20-30%.

The EIA DPR reports on 7 major tight oil and gas regions, which each produce a varying mixture of oil and gas (see map at the top). Based on the mixture of hydrocarbons yielded, it’s useful to split these regions into two groups: the 5 oil-dominant regions of Permian, Eagle Ford, Bakken, Niobrara, and Anadarko and the 2 gas-dominant regions of Appalachia and Haynesville. While 45% of natural gas production does come from oil-dominant basins, less than 2% of oil production comes from gas-dominant basins; for the purposes of this oil-focused discussion, we’ll mostly be leaving Appalachia and Haynesville for another day.

So, what gives in the Permian Basin? If you look closely at the above chart, we can see that Permian oil production has considerably outpaced the recovery in drilling rigs. Part of what we’re seeing is a genuine increase in rig productivity similar to what we’ve seen in previous market routs: as prices fall and rigs are idled, the best remaining rigs and crews become concentrated in the best geological acreage. But another important ingredient is that the implied rig productivity in the Permian basin is being juiced by the depletion of drilled but uncompleted (DUC) well inventory.

What the DUC?

The state of US tight oil production is actually worse than it first appears. Current production rates, especially where we’re seeing any tangible recovery (i.e., the Permian basin), are being subsidized by a rapid depletion of DUC inventory.

Drilled but uncompleted wells are a function of the fact that the US shale production process has two major steps: (1) a well is drilled with a drilling rig and then (2) it is “completed” by a different team (i.e., the actual fracking part) after which it begins to produce marketable crude. When drilling runs ahead of completions as it largely did through 2017-19, the industry accumulates a sizable mountain of this potential production. These DUCs were yet one more bearish factor weighing on pre-COVID market prospects: even when US drilling declined, producers could lean into their DUC inventory to keep production humming along despite weaker rig activity.

And in the 2020 downturn, this is exactly what happened. Rigs across all regions were idled and production collapsed. When the industry began revving up again near the end of Summer 2020, completions ran well ahead of drilling, drawing down that fracklog—er, backlog—at a record pace. This DUC drawdown, especially in the Permian basin, essentially subsidizes still-weak drilling activity, making rigs seem even more productive.

Drilling remains down, if not non-existent, across all oil-dominant regions of the US shale patch, even in the Permian Basin where producers are technically setting fresh all-time production highs. This means that the current medium-term prospects for US shale production are lackluster to say the least barring a material acceleration in rig activity. And this is amidst favorable price conditions begging the question of what it will take for US producers to put in the investments required to contribute significant additional supply to the global oil market over the next year.

Great piece

I am here because of the great paranoid green chicken. As someone new to markets, I wanted to ask, what books would you recommend for someone interested in fully understanding your work? Also, why don't you have 5000 subs yet? (I am sure you will get there).