Oil Strong but Headwinds Mounting

Crude market is tight and inventories falling but transitory COVID, sentiment headwinds building

Crude prices reached fresh pandemic-era highs of $85 per barrel (WTI); oil continues to see strong fundamental support, yet headwinds are building.

Oil market strength persists in the form of acute futures backwardation, continued drawdown of global inventories, recovering refinery margins, and a generally bullish environment towards all fuels amidst multi-headed global energy crises.

But this rally is now obviously longer in the tooth than in August and near-term risks are building: the trajectory of COVID feels like it can only worsen through winter and we’re back into clearly stretched speculative sentiment territory.

Oil prices are really, really high again—you’ll hear a lot of “highest since 2014!” these days—and I thought this would be a good time to follow up on my last two higher-level oil market updates.

My first newsletter in late-June, The Oil Market is Super Tight—But Also Not At All, was balanced but broadly skeptical of the rally, highlighting that still-reasonable oil inventories, weak product markets, and excessive speculative positioning were all putting near-term risks to the downside. Prices fell by $13/bbl between early July and mid-August.

My next update, Crude Healthier Today Than When Prices were Higher, on September 1st got more bullish on the back of rationalized and fleshly-primed speculative headroom, COVID deceleration tailwinds, and more certainty regarding OPEC+’s production outlook. Prices rose $16/bbl from that publication to $84 per barrel as of writing.

Despite fear of inevitably ruining this lucky publication streak, I wanted to revisit some of those key indicators that I reviewed for the previous market updates. I should note that the time horizon on these drivers is quite short-term (i.e., next few months). I maintain a higher conviction longer-term bullish outlook on weak supply growth prospects (which I’ll hopefully write up soon).

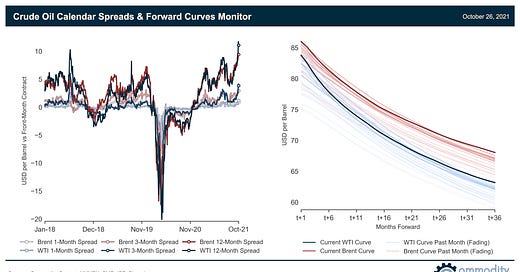

Crude’s Post-COVID Calendar is Tight

First, calendar spreads have moved into even steeper backwardation (see first chart for how far spreads have widened). I noted in my very first newsletter that calendar spreads—or the difference between various vintages of futures contracts—are a great directional indicator about the state of a commodity market like oil. As is the case now, spot prices that trade at a premium to future-dated barrels is known as “backwardation” and this is fundamentally bullish for markets as it reflects insufficient spot supply relative to current demand. Holders of inventory cease to be paid to store crude and are instead incentivized to release barrels to the market to fill the perceived production hole.

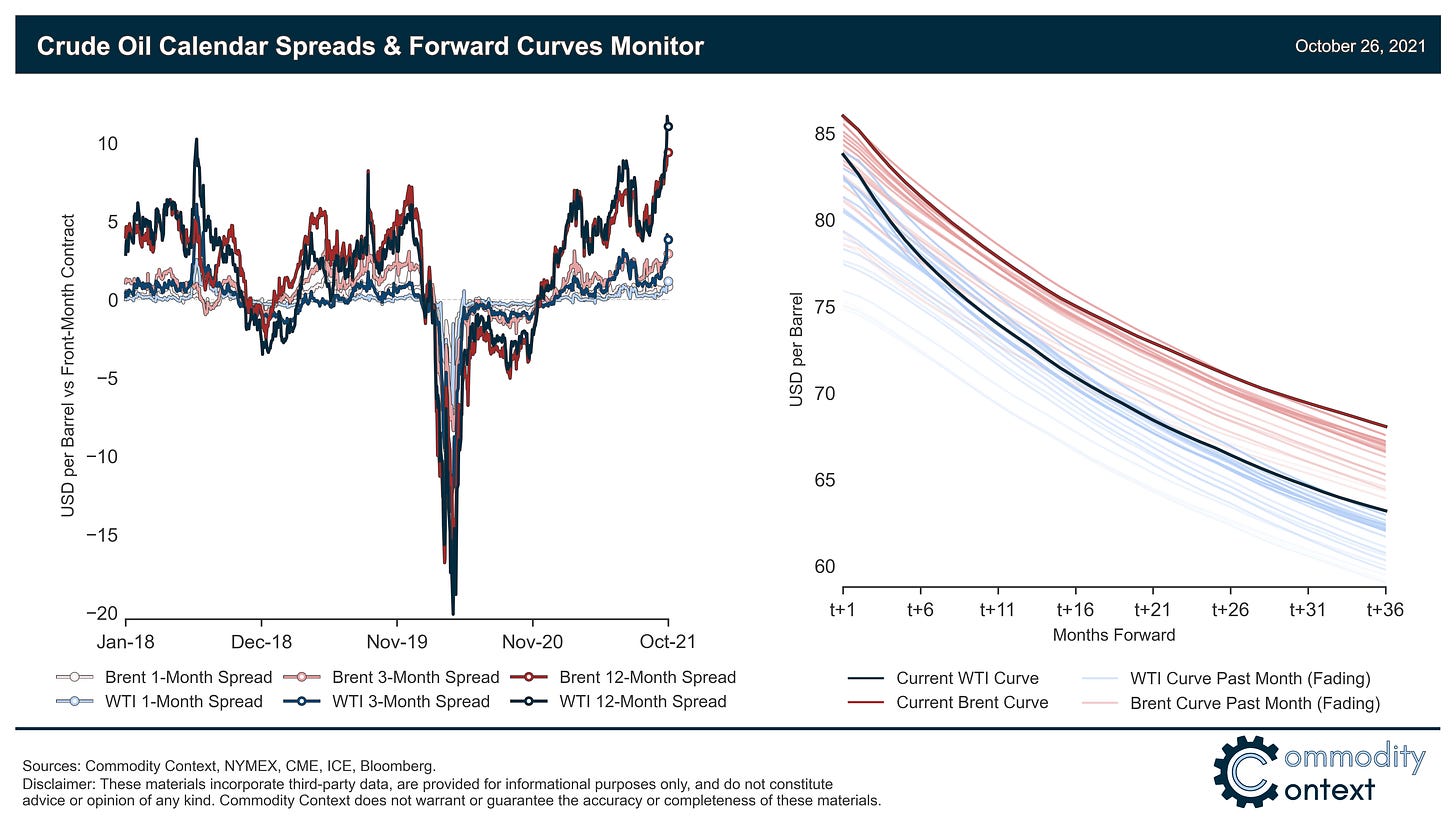

The acute backwardation facing crude markets today remains the strongest signal of insufficiency-supplied markets, and inventories continue to draw down rapidly around the world. In fact, OECD commercial crude inventories fell by a record 400+ million barrels since August 2020, more than erasing the pandemic-induced inventory glut. This drawdown rate is matched only by the scale of inventory builds during the cycle that tanked oil prices between 2014 and 2016.

But in such tight and precarious markets as we find ourselves today, I think it is also easy to overstate the fundamental value of rapid moves in calendar spreads, especially blowouts in intraday trading at the front of the curve. Recall that the reason timespreads are important is that they give us the rough direction and magnitude of inventory movements, but that sporadic moves throughout the day are more noise than signal. Even while writing this piece, the WTI prompt-spread (i.e., the difference between the front-month and the second-month futures contract) blew out from about $1.30 to $1.70 before collapsing back to around $1.15 in the span of just a few hours. That degree of volatility smells more like futures positioning and risk management activity than it does a true sign of a rapid change in the magnitude of the undersupply faced by the market, though the direction of spread movement remains constructive.

This sense of spot market tightness is exacerbated by the ongoing energy crises linked to tight natural gas, coal, and power markets across Europe and Asia. These multi-headed energy crises have the potential to contribute upwards of a million barrels per day of fuel switching demand, on top of the broadly bullish effect of the feeling of global scarcity on current sentiment. Demand has also continued to recover and, with the help of that aforementioned fuel switching, refining margins have roughly doubled from August levels, which further eases concerns about lingering weakness in end-product markets.

Crude vs COVID: Winter Wave Worries

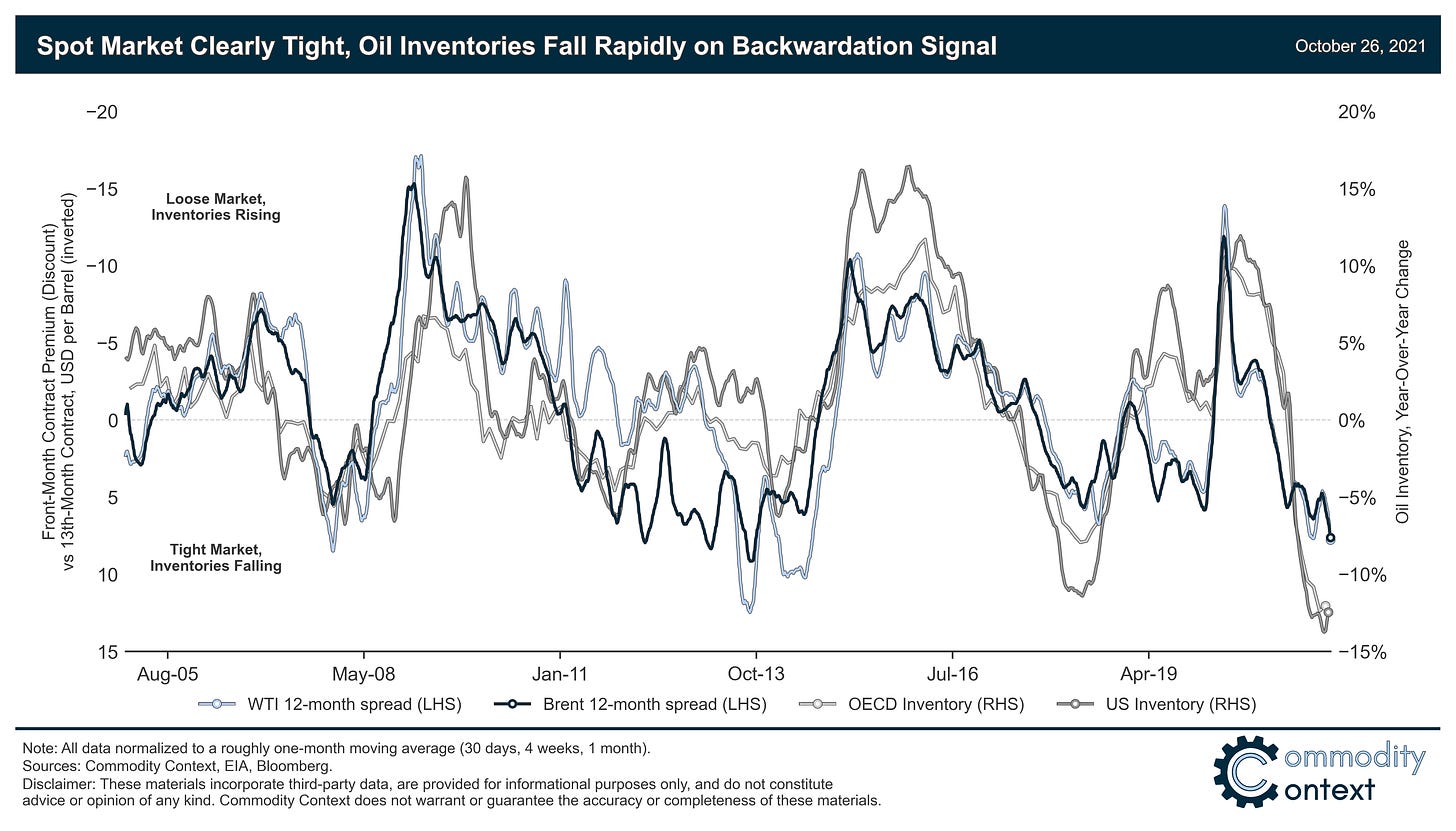

Lower COVID case counts are obviously a great thing; however, at this stage it feels like developments over the winter can only get worse. As I first discussed in September, the year-to-date relationship between crude prices and global COVID case counts has more to do with investor sentiment than demand for oil products (although there is also a direct impact as outlined in my oil demand recovery piece here). As it currently concerns those interested in the constellation of factors driving the global oil market, COVID has shifted from a bullish to a neutral-to-potentially-bearish factor for crude.

See, the rally that took us to the highs of late-June was driven in part by rising risk appetite amidst falling global COVID cases. Then around the end of June, global COVID cases began to rise again, which coincided with a $13/bbl drop in the price of crude through mid-August. The high point of global cases marked the low point for crude prices in mid-August, after which both trends reversed with global case counts falling and crude rallying to set new pandemic-era highs above $85/bbl.

As for current global COVID case counts, we’re just coming off the bottom of another wave and it doesn’t feel possible to see much more improvement absent complete eradication (if wishing made it so…). We will likely see worsening global case counts next, an outlook made more probable as we head into winter and already see new infections gradually accelerating once again. The counter to this cautious COVID narrative is substantially higher vaccination rate: the number of global COVID vaccine doses administered has doubled since mid-July. Still, it remains to be seen if that higher vaccination rate will materially blunt the emergence of another winter wave and, with it, the market’s inevitable reaction.

Hot Money Rolling or Just Taking a Breather?

As discussed above, the effect of macro and COVID concerns on crude prices has been primarily via speculative sentiment. The net position of speculators, as measured by Commitments of Traders reports, fell by roughly one-third through the July-August rout and coincided with a WTI price loss of about $13/bbl. As positions began to rise anew, oil price gains far outpaced their relative losses and rose almost twice as much as they had fallen despite only recovering about 60% of the liquidated length, indicating that the latest rally was driven by more than just hedge fund interest.

We still have room to go to hit the level of net length witnessed in late-June. This leaves fuel in the tank for further bursts higher; but it is also undeniable that we’ve re-entered a frothy sentiment environment in which the downside rationalization risk is ever present. In fact, it looks like net positions have already begun to roll over from the latest cycle high-water mark left at the beginning of October. The fact that crude prices haven’t collapsed outright is a positive sign of the market’s current resilience.

Oil remains fundamentally well-supported as evidenced by tight calendar spreads and rapidly falling inventories. However, a constellation of shorter-term factors like the trajectory of the pandemic and speculative sentiment tip near-term risks to the downside. The ongoing energy crises around the world and the spectre of an especially frigid winter may be enough to support crude prices through what are expected to be temporary headwinds.