Hot Gas Summer

Natural gas prices are running hot and it ain’t even cold yet

Gas prices are rallying together globally and during the summer, which are both notably weird.

In North America, while natural gas inventories aren’t especially low at present, the combination of unrelenting export demand and producer hesitance to lift production has the market spooked.

It’s useful to think of currently lofty prices as the market testing this newfound producer restraint and a hedge against the possibility that export demand just doesn’t let up or the eventuality of especially cold winter.

North America’s key Henry Hub natural gas price benchmark is at its highest level since 2018. That statement actually downplays how high prices are right now: Henry Hub is at its highest summer price level in a decade. Even more remarkable is the fact that this price boom is occurring globally, whereas natural gas is normally a highly region-specific market given the difficultly and expense of trading across oceans (or really anywhere outside a pipeline). I recently chatted about the boom on BNN here.

So, why are prices so high? I’ll focus here on the Henry Hub benchmark because I don’t want this to drag; but don’t worry, I’m sure I’ll get to LNG markets soon enough.

Natural gas inventories have fallen quickly through 2021 after a fairly glutted 2020

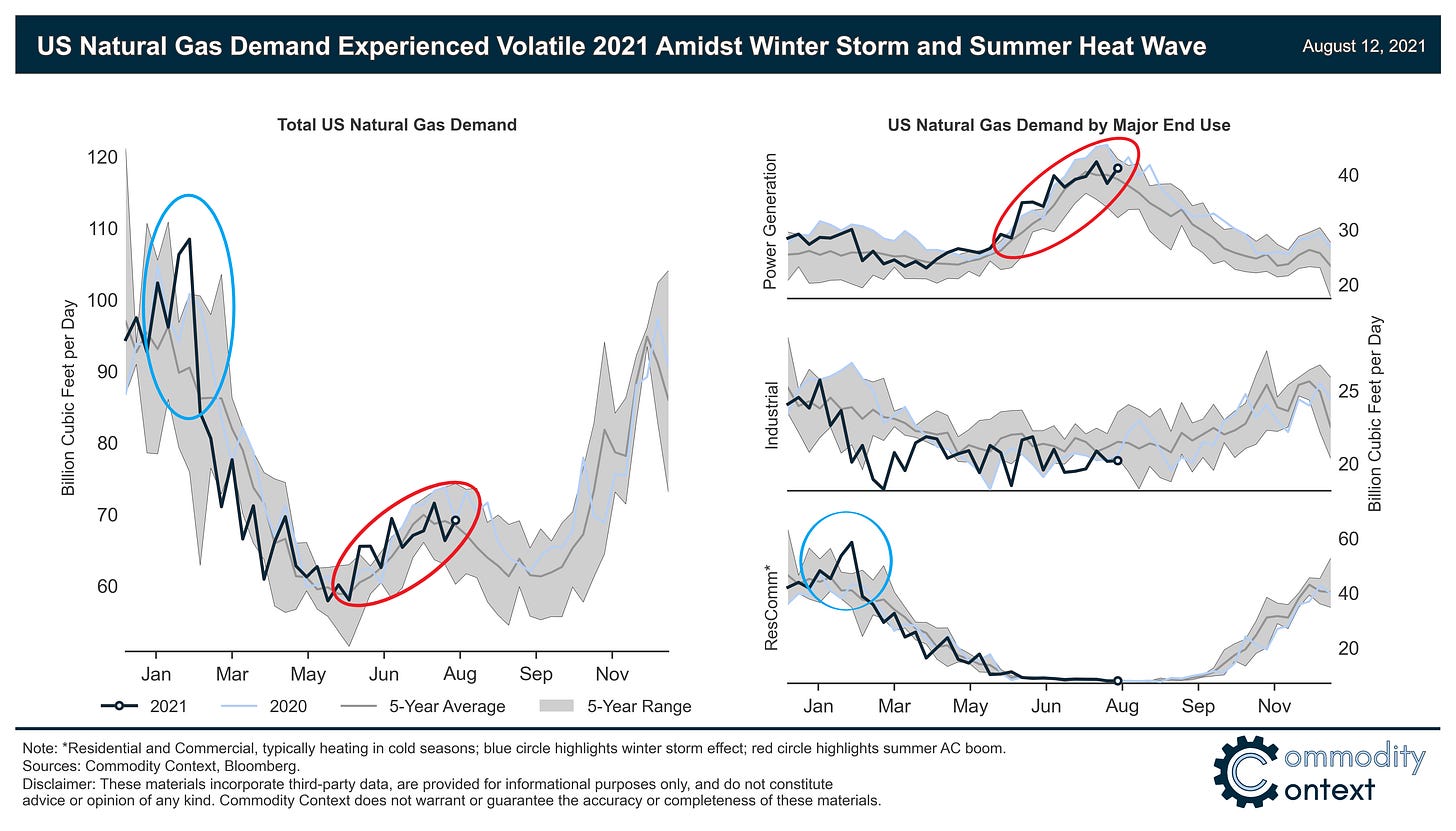

First, its important to understand that natural gas demand is highly seasonal, with much higher consumption for heating in the winter than for power generation in the summer. Production, meanwhile, is much steadier throughout the year. Balancing the seasonal mismatch falls to inventory management: stocks are typically built up between April and November and then draw down from November to April.

Inventories started 2021 near the upper end of their 5-year range but fell precipitously to below 5-year average levels in February as a result of the winter storms that roiled much of the US and were especially acute in Texas. Not only did heating demand skyrocket, but temperatures dropped so low that gas producers experienced so-called “freeze-offs” that cratered natural gas production just when it was most needed. In little more than a week, the winter storm blew through what had been a healthy volume of buffer stocks and primed the market for prices to rise to the levels we’re seeing today.

Cold winter, hot summer kept demand strong and inventory injections weak

The winter freeze (blue circles on the chart above) was followed by a blisteringly hot summer that kept demand from the power generation sector well above typical levels as North Americans ramped up air conditioner use (red circles). US consumption has since normalized with the assistance of high price pressure, but export demand—a relatively new but increasingly material factor for gas markets—is surging with no end in sight.

Exports are ripping with no end in sight

US exports of natural gas—both via pipeline to Mexico and via LNG to global markets—are setting all-time records. In normal times, the economics of exports (especially pricier-to-process LNG) would strain under rising feedstock prices linked to Henry Hub and then facilitate some degree of natural pressure release for the market. However, as discussed at the outset, this gas boom has been global in scope and prices would need to rise much, much higher to make a dent in potential liquefaction margins amidst LNG prices in the $15 per MMBtu ballpark through much of the world. China, Brazil, India, and South Korea have all recently imported record volumes of LNG. Furthermore, there really isn’t any slack in the global gas production system, save Russia, which seems unlikely to lift gas exports to Europe before the approval of the geopolitically contentious Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

US supply response restrained by newfound producer discipline

This combination of robust domestic demand and surging exports wouldn’t have been such a challenge in the past. In fact, the North American natural gas market has felt the pressure of unrelenting and seemingly endless production for much of the past decade with prices far lower than they are today. The two greatest sources of that production growth have been the prolific shale gas basins—especially the mammoth Marcellus Shale in the northeastern US—and gas produced as a by-product of tight oil production—particularly in the Permian Basin across west Texas and eastern New Mexico.

Fast forward to today, however, and the situation has changed. As discussed in my first newsletter on the crude market, US producers have yielded to equity market pressure to resist growth-focused investments and prioritize cashflow. Combined with COVID-walloped prices in 2020 and the resultant uncertainty, US natural gas production fell back and isn’t expected to exceed pre-COVID levels despite currently lofty prices until the fourth quarter of 2022 at the earliest according to the latest forecasts from the US Energy Information Administration.

In short, natural gas prices are high today because demand remains robust, weather has been unforgiving, and producers don’t seem that interested in drilling more any time soon despite attractive margins. The saving grace for natural gas consumers is that inventories remain at a reasonably safe level for this time of year. But that inventory safety could be jeopardized if exports keep rising or we have an especially cold winter the market, which would push markets into a more precarious position in a few months’ time.

Think of today’s high price as a test by the market: will producers take the bait and drill again despite their recent restraint commitment? Will exporters let up? Will we catch a break in the form of a mild winter? Let’s check back in a few months.