Canada’s Zombie Pipeline

Like a zombie, Keystone XL just won’t die; the pipeline is simply too symbolically important to ‘rest in peace’, but even in theory it’s a mixed bag for Canada versus the alternatives.

If you’re already subscribed and/or appreciate the free summary, hitting the LIKE button is one of the best ways to support my ongoing research.

Keystone XL is stirring in its grave once more and this latest resurrection of the pipeline must be understood in the context of Canadian appetite for diversification away from US dependence after the second election of Donald Trump and, specifically, ongoing threat of tariffs.

Additional pipeline capacity into and/or through the US (a la Keystone XL) is, likely, the easiest to build and most commercially viable; however, Keystone XL offers the least additional energy security benefits for Canada—not to mention that corporate appetite is very low at this point.

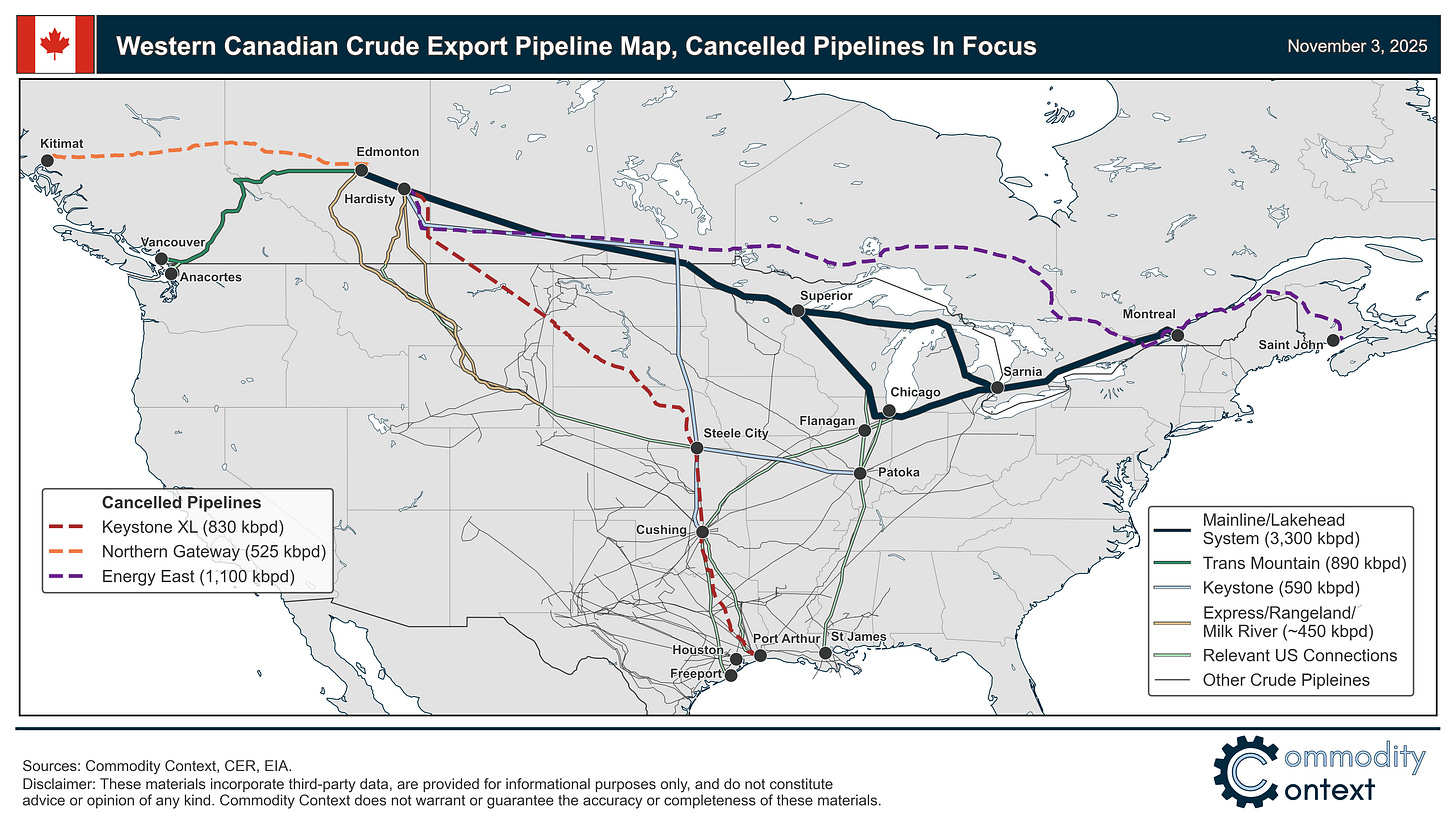

Keystone XL is not the only option for increasing Canadian crude egress and export diversification: a west-bound pipeline (e.g., Northern Gateway) would bolster Canadian security of demand while an east-bound pipeline (e.g., Energy East) would bolster Canadian security of supply, especially for Ontario.

It’s highly likely Canada will, soon, overrun its newly expanded pipeline capacity and, with the national narrative shifting in favour, this is a key opportunity to build a—as in any—new pipeline; but, the odds still feel stacked against Keystone XL, specifically.

In the spirit of Halloween, the “zombie pipeline”, Keystone XL, has, once again, been making headlines. The subject of recent industry journalist enquiries, Keystone XL is likely the North American pipeline with the greatest name recognition—especially strange since it doesn’t actually exist. The proposed pipeline was cancelled by Obama in 2015, reincarnated by Trump in 2017, killed again in 2021 by Biden, and there is now talk between Trump and Canadian PM Carney of trying to build the pipeline once more. Keystone XL would shuttle western Canadian heavy crude toward the US Gulf Coast; but, the project has faced (arguably, kickstarted) the now commonplace practice of environmental groups targeting midstream projects as a means of opposing upstream oilsands development.

However, we would argue that this latest resurrection of Keystone XL must be understood in the context of Canada’s renewed push for another pipeline project. In this vein, Keystone XL is not the only direction for growth: there are two other legitimate directions that a future Canadian liquids pipeline could run. All three directions—south to the US (e.g., Keystone XL), west to the Pacific coast, or east to Ontario en route to the Atlantic—each come with idiosyncratic benefits and drawbacks, as well as historical baggage.

So, let’s contextualize the current debate around Canada’s “zombie pipeline” and the potential of a new Canadian pipeline, more broadly.